Neither Forgone nor Forgotten

Post-MPI reflections on Trauma, Forgiveness, and Reconciliation

I’m seeing that it’s been nearly a year since I’ve posted here, but I suppose my recent uptick in long-distance flights and stays at Korean saunas have brought me back to writing on this medium (in fact, I’m writing this at King Sauna in New Jersey, which has now become a place of respite, reunion, and reflection). I also have a lot to digest (literally and figuratively), as I’ve spent the past 2 weeks at the Mindanao Peacebuilding Institute in the Philippines, where I took a course on Trauma-Informed and Resilience-Oriented Practice and a course on the Praxis of Forgiveness and Reconciliation Amid Polarization (thanks to the generous support of the Kroc Institute and the Pacific Century Institute!). I am also so grateful to the MPI secretariat, facilitators, venue staff, and fellow participants who welcomed, inspired, and challenged me. Though it’s hard to capture the essence of such an eventful fortnight, let’s see if I can still write “normally” after a year of being disciplined by the structures of academic reading and writing…

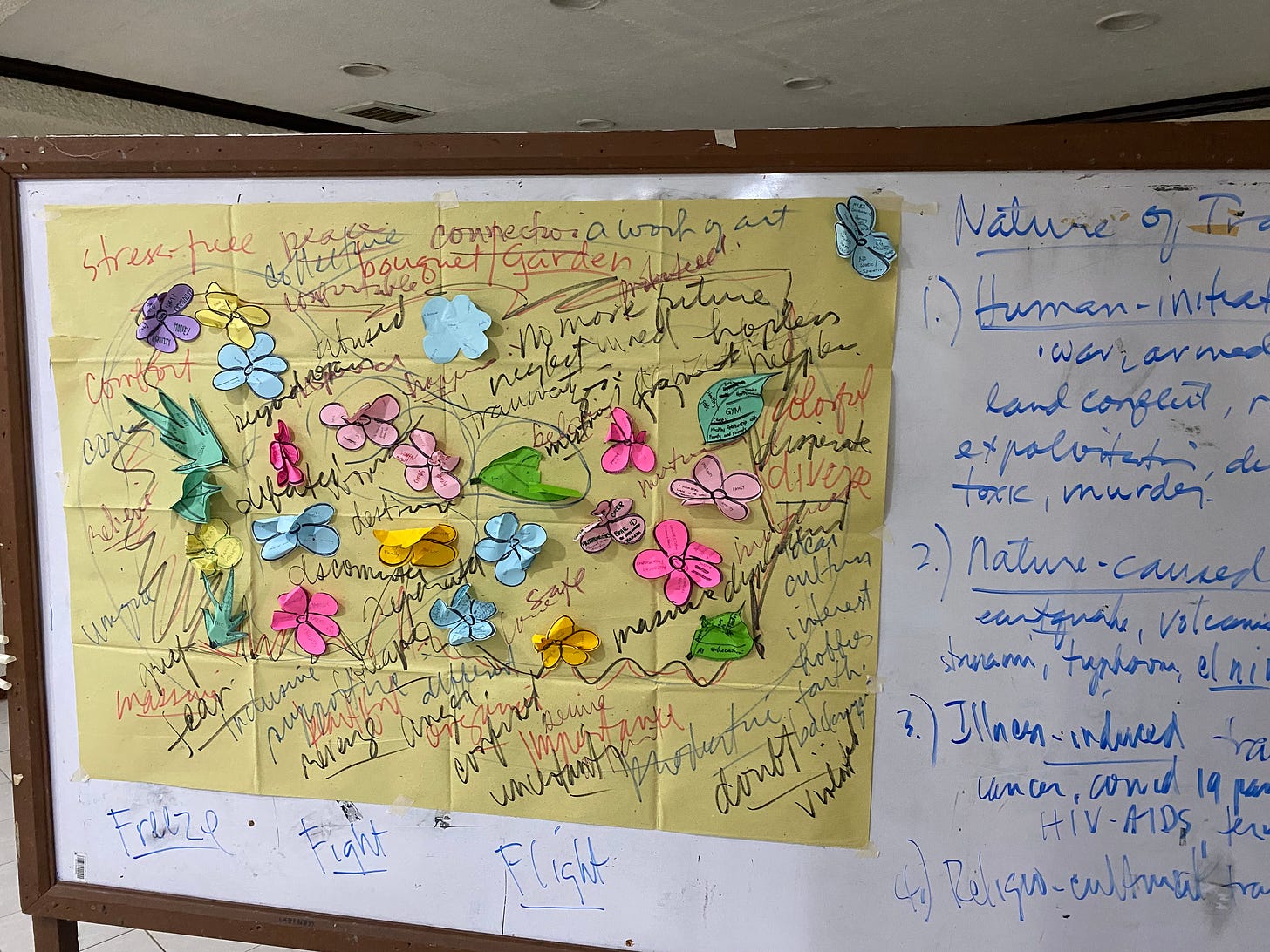

Scenes from MPI (photos from myself)

Overall, I would say that I am left feeling humbled, reinvigorated, and connected by what I saw and heard from my fellow participants, who included staff from the Philippines’ Office of the Presidential Adviser on Peace, Reconciliation and Unity (OPAPRU), representatives from various indigenous communities in the Philippines, Buddhist monks from Laos, and colleagues from Germany’s Civil Peace Service. While I had heard great things about MPI – which was celebrating its 25th anniversary as a hub for training peacebuilders from all over the Asia-Pacific – from friends from the Northeast Asia Regional Peacebuilding Institute and the Kroc Institute, I was amazed by the unexpected synergies that I found in new friendships and encounters: a sign that we are walking the right path. It was not only a re-grounding change of pace to leave my academic bubble at Notre Dame and enter into new rhythms – albeit temporarily – with people for whom violent conflict and poverty are part of their everyday life. Most of all, I felt connected to the nodes of a broader movement – stemming back from Eastern Mennonite University’s Summer Peacebuilding Institute, which served as a model for programs like MPI and NARPI – of peacebuilders engaged across borders of time and space.

Action shot from the closing ceremony of MPI (taken by MPI staff)

On one hand, the vibes were quite familiar, like the cultural curiosity and warm energy I had felt at the United States Institute of Peace’s Generation Change Fellows Program trainings or at NARPI trainings across Northeast Asia (adding in some extra karaoke, seaside meals, and new flavors like durian and tubá). On the other hand, I was very much an outsider, as one of the only individuals hailing from the United States and given the additional responsibility of representing South Korea (a part of me that was celebrated like I’ve never seen before in my life). Seeing how people’s faces lit up when I told them I was Korean, proceeding to profess their passion for Korean dramas and Kpop idols – left me dumbfounded of this newfound “Korean privilege” that I didn’t even have growing up in one of the biggest Koreatowns in the US.

The centerpiece of the classroom: a “wave of love” plant (which endured the heavy air conditioning better than I did)

Anyways, given that the point of trainings like MPI is for participants to take lessons back to their own communities, I thought it might be valuable to reflect on what I thought were the most salient learnings as we continue “Phase 2” of the Letters to My Hometown Project this summer in New York and Los Angeles, this time featuring conversations between elderly Korean Americans and their grandchildren.

TRAUMA(S) and how we deal with them

Though I’ve written about “han” before here, I’ve felt that it’s one of those terms that has almost become a wee bit cliché to describe the sorrow held by “the Korean people.” That being said, it’s interesting to look at the etymology of the Chinese character – 恨 – and see the character for “heart” on the left and a character that means “tough” or “stop/pause,” and looks like a person peering over their shoulder. Perhaps this kind of wound has us stuck in our hearts and constantly looking back to the past. I think I prefer another word that one of my interviewees mentioned – 응어리 or eung-uh-ri, which refers literally to a knot in one’s muscles or figuratively to an unresolved issue lodged in one’s heart.

In any case, I think it’s clear that many people – whether Korean or not – experience this kind of trauma, whether on an individual or collective level. However, I think what makes case of Korean American divided families exceptional is that there is an intersection of so many sources of trauma – including experiences of Japanese colonialism, displacement from hometowns and separation from family in North Korea during the Korean War, poverty and military dictatorships in South Korea, to alienation as immigrants in the United States. They have not only faced marginalization in society, but also with their own children and grandchildren, with some of whom they do not share the same language or faith. As I’m starting to understand just how complex the traumas of the Korean American community are, I am realizing that one intervention will not be “enough” to break through these cycles of violence and silence.

I do think it is worth discussing the “typical” way Koreans have been lauded for dealing with their “han” – through 인내/innae, which can be translated as “patience,” “perseverance,” or “fortitude.” If you look at the Chinese characters, though – 忍耐 (each meaning to “endure” or “bear” something) – you will see a knife held above a heart in one character, as well as two characters that spell out “and another inch.” This is exemplified in films like “Ode to My Father,” which laud the virtues of sacrifice despite suffering for the sake of one’s family and nation. Yes, gritting one’s teeth and enduring may have led to economic prosperity, safety, and stability…but at what cost?

I would argue that freeing ourselves from the multiple “hans” of history requires transforming the culture of 인내/innae toward one that loosens the grip of those knots on our bodies and souls. Could it be through 정/Jeong/情? The connotation of the Korean word of the Chinese characters for letting one’s heart free(放心 방심), however, is being negligent, absent-minded, or even underestimating. What would it take for one’s heart to truly be at ease (安心 안심)? I sadly don’t have the answers now, but I think I’m asking better questions…

FORGIVENESS: it was there all along

While I was learning that forgiveness – the decision to let go of bitterness, anger, and resentment – was key to finding freedom and a sense of agency, I really struggled for most of the two-week program to find the concept of forgiveness relevant for Korean American divided families. For unlike in the rido of revenge killings between communities in Mindanao or the Rwandan genocide, it is difficult to assign a name or face to a single “perpetrator” for an event like displacement or family separation. Who would these elderly Korean Americans need to forgive – the North or South Korean military? US or Soviet government officials?

It was only when I rewatched clips from the interviews I did two years ago that I noticed that when I asked interviewees, “what do you want to tell your family in North Korea?” many of them would get emotional and say how sorry they are for not being able to visit them again, or for the fact that only part of their family was able to leave the country. Perhaps behind these apologies were feelings of unresolved guilt, contrition, and self-blame that I believe reflect a desire to be forgiven by their family members (even if it was not their “fault” that they were divided).

Perhaps the intergenerational conversations this summer can also provide spaces for grandchildren to “forgive” their grandparents for whatever harm that was done through this culture of silence, shame, and endurance. Even from recent experiences with members of my own family, I am starting to accept that forgiveness is possible even without explicitly saying the words “I forgive you.” Rather, if we understand forgiveness as “the final form of love” (attributed to Reinhold Niebuhr),” perhaps we can find forgiveness in ordinary and extraordinary gestures, such as unexpected tears over a homecoming meal.

RECONCILIATION as a Bittersweet Symphony: Transcending Polarization and Translation

The Statue of Brothers at the War Memorial of Korea in Seoul (photo by myself)

From statues of two individuals embracing in Belfast and Seoul, or even in artwork like Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son, it seems that the most popular image of reconciliation features a dramatic in-person reunion event. But what does reconciliation look like if one or more parties are no longer alive or able to reunite (such as in the case of Korean American divided families)? I am trusting that reconciliation is still possible even while structural barriers like division and conflict are still in place – a more spiritual kind, and one that requires a radical transformation of the “ideal” of reconciliation. I am becoming increasingly affixed on “transcendence” as the key to truly healing from the wounds of conflict – not simply resolving or managing trauma, but finding the strength and solidarity to rise above a singular story of victimhood.

Reframing Psalm 85, John Paul Lederach describes reconciliation as the “meeting place” of Truth, Justice, Mercy, and Peace. But what if there are multiple versions of “truth,” different struggles toward “justice,” various levels of “deserving” mercy, and politicization of the term “peace”? Given the numerous understandings of such broad terms that are often lost or misinterpreted in the process of cultural translation (like in the US or South Korea, where the very concepts of “truth” or “peace” spark entrenched divisions in society), it is clear that multiple versions of each of these concepts (the various Truths, for example) need to reconcile with themselves before they can begin the process of reconciling with each other.

The Gymkhana at the Elisabeth Morrow School, one of my first experiences of playing in an orchestra (photo by EMS)

What, then, would be a more appropriate image to represent the process of reconciliation – one that can reflect its temporal and multitudinal complexity? Perhaps it could be a quilt (like Chilean arpilleras or those made by Mennonites), a free-form dance circle, or a lush garden. From my own experience playing cello in groups my entire life, I would have to describe it as a chamber orchestra (coordinating among themselves without a conductor), beginning with each section going from utter cacophony to tuning (perhaps the brass section could be truth, percussion section could be justice, the woodwinds could be mercy, and the strings could be peace) to producing a collective sound that can be witnessed by an audience and recorded for posterity. Some orchestras are bigger and better funded than others, while some play certain kinds of music in opera halls to open-air venues. But even when they play the same piece, I’ve appreciated how each rendition is different, resonating more with some than others. To me, this miraculous process of harmonization of sounds and bodies breathing in sync without everyone having to play the same note or instrument is the essence of reconciliation. For now, let this mark an “intermission” and please stay tuned for the next movement of this ongoing symphony…

Paul, this is such a profound articulation of your experiential learning at this year's MPI. I appreciate the depth and breadth of this reflection piece. I felt like I journeyed with you while reading and reminiscing our time together at MPI. Truly insightful and reflective. I will quote your conceptions in the article that I am writing on Re. Han and Trauma, if thats ok. Continue the journey..

. I will. Thank you.

Great to receive this Paul and thinking of you this summer