On severance, wholeness, and home

A roundabout reflection from the East Coast

As I’m starting to write this on a flight from Newark to Japan, the plane that I’m on is just about leaving the continental United States (off the coast of Alaska into the Pacific). I’m headed to Hiroshima and Nagasaki as part of a US Catholic university delegation to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombs. I’m sure I’ll have a lot more to write about after this trip, so I wanted to try to distill my thoughts and feelings from the past two weeks’ interviews from the East Coast before they are overshadowed by newer ones.

Fittingly, the show that I’m watching on the plane is “Severance” (thanks Cedric for the recommendation!), which is set in a world where employees at a company choose to be “severed” from memories of their workplace outside of the office building. I wonder, would this selective amnesia of one’s hometown or family members in North Korea be preferable to the lingering scars of separation? While none of the interviewees so far have had Alzheimer’s or dementia, many struggle to remember the contours of their childhoods 75-80 years ago…yet at the same time, they remember certain details clearly – such as their home addresses (down to the exact street), the Japanese names they had to use under colonial rule (1910-1945), and where they were on pivotal dates like August 15, 1945 (when Korea was liberated from Japan) or June 25, 1950 (the start of the Korean War).

“Severed families” doesn’t quite have the same ring to it as “divided families,” but it does feel like a more appropriate word to describe what happened to so many Korean families on the Peninsula and in the diaspora. Our society prefers to count things – the number of casualties on the battlefield, the dollars gained or lost from tariffs, or the years and decades of an enduring conflict. I get why labels like “ten million divided families” to describe the number of families separated from the Korean War (the validity of which James Foley has rebutted) or 100,000 Korean American divided families (based on approximating census data and statistics on Korean divided families from the early 2000s) have stuck. On the other hand, I’m realizing through this project that it is hard to standardize or even quantify the impact of severance on a family, much less on a nation. I’m reminded of Pádraig Ó Tuama’s poem “The Pedagogy of Conflict” and how each family is affected by and deals with displacement from one’s hometown in their own way.

Reunion is not free: the emotional and financial cost of rebuilding family ties

Last night, I watched a heart-wrenching and warming film called “Between Goodbyes” at the International Asian American Film Festival in New York City (thanks to Youngsun and KAS for the opportunity!). I laughed and cried through intimate scenes of a Korean woman who was adopted as a baby by Dutch parents as she mends broken ties with her birth family. Though I was relatively familiar with the challenges of transracial adoptees through working on the Divided Families Podcast, what was incredible about the story is that it is not just about a one-time reunion – rather, the film shows how the process of rebuilding relations takes decades of translated letters, video calls, and in-person gatherings in Korea and the Netherlands.

At one point, an advocate for mothers who gave up children for adoption says, “perhaps reuniting and saying goodbye for the second time requires more grieving, because it forces us to face what has changed and what was lost” (my translation from Korean). In other words, mending a relationship that was ruptured by adoption or displacement requires intensive emotional effort over time (James Foley has also written about the harm that the one-off inter-Korean reunions can do for families who have to say goodbye again, but for good). At the same time, Mieke (the protagonist of the story) says she felt an immediate kinship with her siblings (even though they speak different languages and are meeting for the first time) as well as a sense of connection to her birthplace and ancestral lineage.

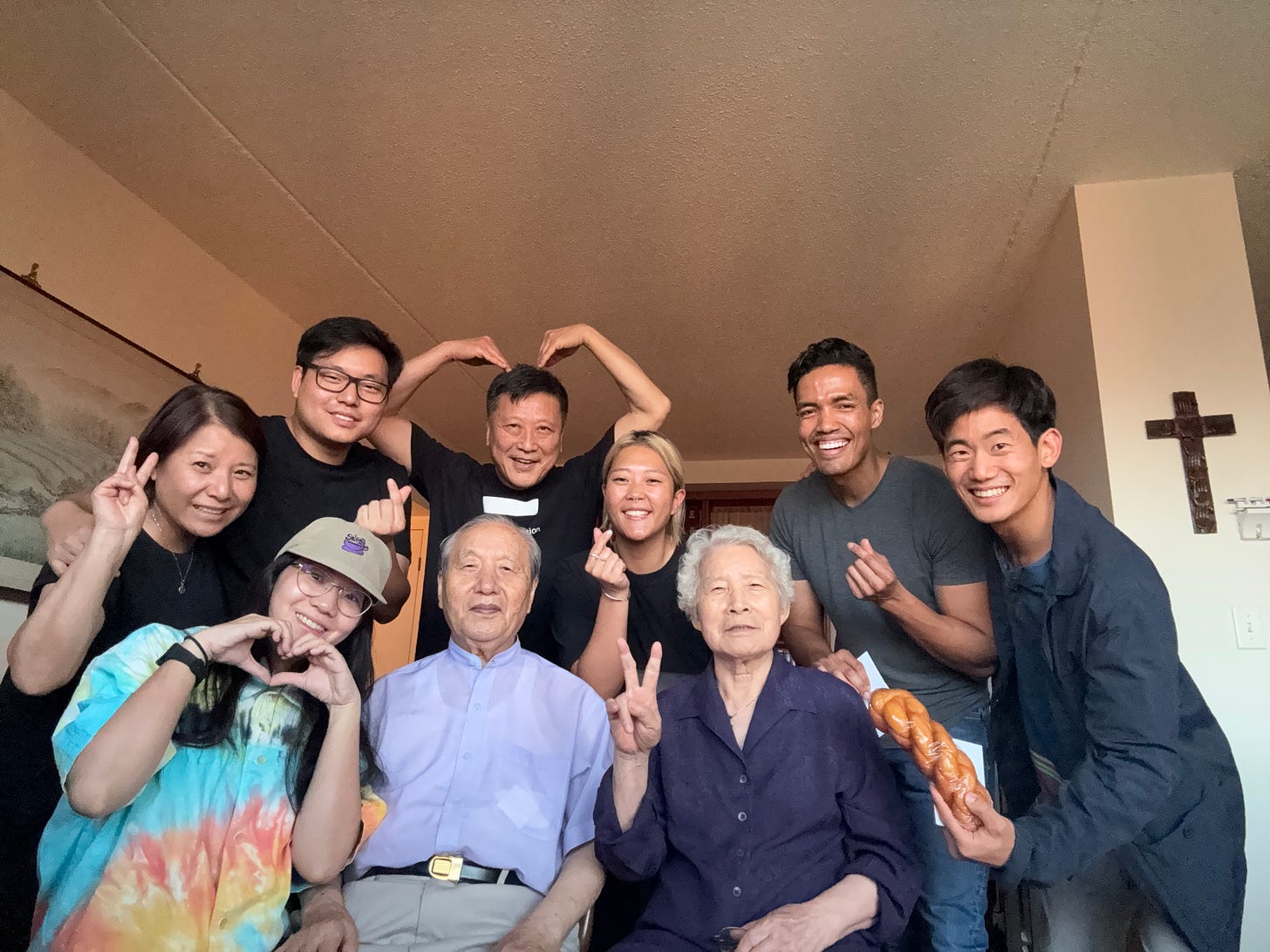

While the context is different, the film made me think of families like Mr. Yun’s, who we got to interview at his son’s home in New Jersey last week. I had known about his story since 2016, when I had watched footage from his 2007 visit to North Korea to reunite with his younger sisters that was featured in the Divided Families Film. Even though Mr. Yun didn’t remember much about his sisters as children (since they were only a few years old when they separated), he said he recognized one of his sisters right away given the resemblance to his mother, though he wasn’t sure if the other woman was actually his sister. He shares about continuing correspondence with his sisters after returning to the United States until he started to feel like the remittances they were requesting were not being sent to them. While remittances are quite common among immigrant families – and perhaps a natural way to show care and support – it is when government interests get in the way that removes the focus from families themselves (you can also see this at play in Susan Choi’s novel Flashlight between members of a Korean family in Japan who split ways to North Korea and the United States).

So while I am all for allowing Korean Americans to travel freely to see their family members in North Korea, I am starting to realize that the act of reuniting (whether as a family or a nation) does not mean reconciliation. In Korean, there can be at least two ways to say “reunion”: 재회(再会)or 상봉 (相逢). The latter is usually used to describe the dramatic North-South Korean reunions (이산가족상봉), whereas the former simply refers to meeting again. Interestingly, the latter also suggests a serendipitous or chance encounter, whereas the former (to me at least) feels more neutral. So, I guess what I am learning (to borrow the language of Father Greg Boyle) is that these elderly Korean Americans’ desire for visiting their hometowns again or for the reunification of North and South Korea are not necessarily ends in themselves; rather, they point to a deeper desire for wholeness and healing.

Toward wholeness as an individual, family, and nation

It is thanks to my friend Michael Roh that I was able to start this project two years ago in Boston. This time, he not only hosted me again but facilitated the interview with Mr. Tae-hyok Kim (born in 1932!), who with his granddaughter Nicole wrote an amazing memoir called Beyond the Border (which can describe the details of his life much better than I can). What struck me was how this man – who has endured separation from his family in North Korea, torture and interrogation by the South Korean military after being wrongfully accused as a communist sympathizer, and a whole new set of challenges upon immigrating to the United States – can have such a gentle look in his eyes and give such warm hugs!

Despite the difficulties caused by a stroke he suffered a few years ago, Mr. Kim was able to read out his heartfelt letter to his parents. He closed his conversation with his daughter and granddaughter by expressing his wish, “that Korea…become…whole.” Not one, not reunified, but whole. Michael had introduced me to a book called “No Bad Parts” about internal family systems (IFS). While I’m far from being an expert on this topic, my understanding is that it involves accepting and integrating all different parts of our self, from the kind to the violent. What would it look like to approach family separation or national division through this lens?

It is impossible to recover the lost time and what-ifs that these families could have enjoyed had they not been separated due to the division of Korea or the Korean War. Individuals have tried to cope and rebuild on their own, whether through solidarity with others who have similar experiences, or by looking forward to the future instead of thinking about the past. But what could it look like to acknowledge and grieve this loss, especially with others who share this experience?

A space to grieve and heal outside of family conversations?

Several, if not most, of our interviewees have been deeply religious, with many having dedicated their lives as pastors in Korean immigrant churches around the US. Accordingly, perhaps the most common response that we get to the question, “what do you want to say to your family and future generations (in the US and North Korea)” is something along the lines of believing in Jesus Christ. As we were finishing up our last interview of the month in Flushing with a 96-year-old pastor, HJ and I reflected on the complexity of the celestial orientation of many people from that generation. On one hand, believing that one’s true “home” is in heaven and that we are only temporary sojourners on this earthly realm could help cope with the pain of displacement or separation. In fact, I remember asking the Dalai Lama (who himself was separated from his own family upon exile to India) a few years ago what he would say to Koreans separated from their families, and he said not to be so attached to the permanence of family ties (which I guess is a very Buddhist thing to say). On the other hand, unless we are enlightened bodhisattvas, doesn’t our imperfect human nature keep us fixed on the land we come from and bodies we are related to?

Since my grandfather passed away in 2014, my grandmother has recited a Catholic prayer called 위령기도(慰靈祈禱), which consists of the characters 위 (“we”) which means “to console or comfort” and 령 (“ryeong”) which means “soul” every single day for the repose of his soul. The prayer consists of a few psalms of praise, followed by an incantation to the litany of the saints for the deceased. At this point, she has memorized the entire prayer by heart, which probably takes about 10-15 minutes to finish. What means more than the words of the prayer is the fact that it has become a ritual of remembrance – something that she does on her own, as well as something our family does together whenever we visit my grandfather’s grave in Paju. Toward the end of Han Kang’s novel “We Do Not Part,” the protagonists uncover news clippings of a 위령 (we-ryeong) event for the bereaved families of targeted by anti-communist violence during the early days of South Korea’s authoritarian rule (in the mid to late 1940s) to remember and lament the loss of their beloved. What would it look like to console the souls of Korean American divided families?

One reason the “grief transmutation circle” from Washington DC two years ago left such a deep impression on me is that I saw Korean people coming together to wail and dance (while completely sober!). Perhaps the biggest challenge that I’ve faced while facilitating family conversations this summer is encouraging those from the oldest generation (especially grandfathers) to talk about their feelings and show emotion. I’m questioning whether conversations – especially those that are recorded and with one’s children and grandchildren – are really the right place for these elders to grieve. Perhaps it is too much to ask someone in their 90s who has never expressed his emotions to suddenly do so, especially in front of a camera and his children/grandchildren. At the same time, seeing how grateful the families have been for the opportunity to have these conversations gives me confidence that it can complement other forms of processing and healing.

Bringing it back home: as people, rather than a place?

I’m realizing how long-winded this is getting (I guess I’m starting to become like the pastors we’ve been interviewing, and the rare opportunity to focus on writing), but I did want to close with one last reflection on home. When I originally conceived the title of this project – “Letters to My Hometown or 고향에게 보내는 편지” – I had assumed that people would have a singular idea of what constitutes their hometown (i.e. their birthplace in North Korea). Well, I sure was wrong. I should have known better, given how difficult the question “where are you from” is for myself, but I quickly learned that responses have varied from Pyongyang to Seoul, from Los Angeles to Toronto, from a farming village in rural Hwanghaedo to the busy streets of New York. Daniel, who has lived in the same apartment building as his mother and grandparents his whole life, said that for him, the dining table where the four of them came together for dinner every day is home, and seeing how hard he tried to communicate with his grandfather in Korean moved me deeply.

One of the best books I read this past year is “Everything We Never Had” by Randy Ribay, which tells the story of three generations of a Filipino-American family (with the help of a dog named Thor) forced to come together and open up to each other during the pandemic. It seems like there was a similar process among many of our interviewees of reaching out to parents and grandparents during the pandemic. I’m understanding that many younger generations of Korean Americans (including myself), connecting and learning more about their ties to (North) Korea is pointing to a deeper longing to connect with their parents and grandparents (despite all the cultural and language barriers), and find a more integrated sense of self.

As we walked around Flushing after the interview with his family, we saw a florist proudly display a photo from Janice’s Han in Town project, which captures the nostalgia of small Korean-owned businesses in the neighborhood. Of course, oral history archives and photographs can save a moment in time, but I do believe that what is generated from the daily rhythms of coming together for a meal or saying the same prayer for 11 years can endure just as much as any video or image. I never thought I’d write out the cliché, “home is where the heart is,” or wax poetic about terms like jeong/정/情 (and I should really wrap up before this gets any sappier), but as my professor Dong Jin Kim said to me recently, perhaps jeong is an attachment that builds with a place or a person over time (whether you want to or not).

That’s how I now feel about New Jersey, whether it is sleepily dragging my feet to mass at the Korean Catholic church, running along the brackish waters of the Hudson with the Manhattan cityscape in the background, or driving back and forth across the majestic steel beams of the George Washington Bridge with the Little Red Lighthouse guiding the way. So this journey (both for this project and my own life) is to be continued, but I will end with this image of a nest that a bird built on our front door in South Bend at the end of my first year there. She constructed the nest with whatever she could find – twigs, a paper straw wrapper, and strands of human hair – to build a home for her eggs. While the eggs ended up disappearing (according to Chat GPT, a predator like a crow could have snatched them), it remains a symbol of enduring love, care, and wholeness in times of vulnerability, uncertainty, and isolation. What are the nests that we have been a witness to in this world, whether they are still physically intact or not?

I’ve made it to Japan now, so I’ll say matane (until next time), rather than sayonara (goodbye forever)!